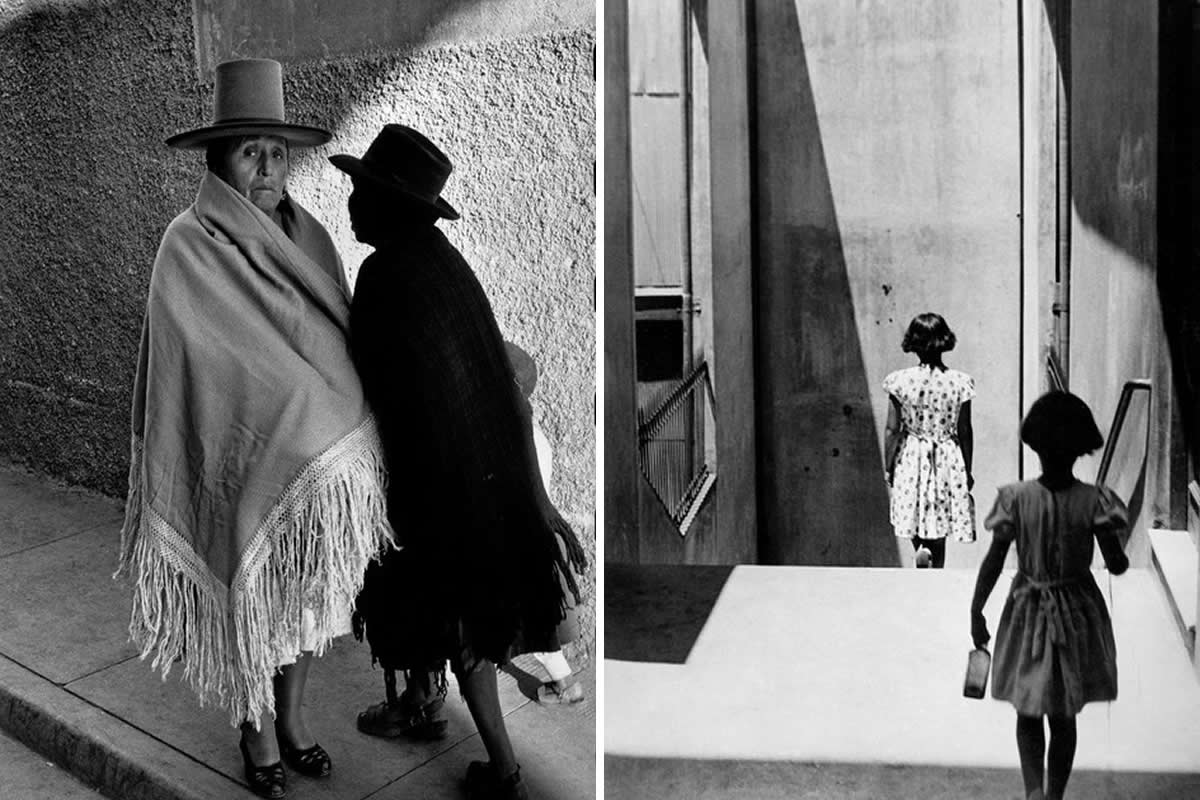

“Wow, what an amazing photograph. What camera do you use?” “I really love your photographs; you must have a very expensive camera.” “Gee, thanks. I use a very old, outdated camera system that’s not very expensive at all.” Let's talk about gear and how it doesn't make you a better photographer.

I'm sure we have all been there. I'm sure these questions have been asked of us all by a great many people. I really can't say that I blame people for asking this question, as the emphasis on equipment is so prevalent in the camera industry with the regurgitation of new gear every year. But in reality, the true craft of photography is not in the manipulation of technology but in cultivating a very unique way to see the world. It really is one of those profound moments in a photographer's journey in this art form when they move away from “looking” at a scene to recognizing the scene's value, structure, light, and narrative.

I am delighted at the opportunity to share my thoughts and insights on the cognitive difference between looking and seeing, how powerful pre-visualization is, and ultimately how the pursuit of personal vision over perfection can make you the best photographer you want to be.

1. The Cognitive Shift: From Passive Looking to Active Seeing

So let's start from the start and briefly discuss the subtle yet very crucial difference between passive looking and active seeing.

Passive looking: I am essentially doing this right now as I write this. I am walking along the road, speaking into my phone (this is how I write), and yes, I am, of course, looking around and being aware of my surroundings—one, so I can hear any potential traffic coming, and two, I am just simply enjoying the nature around me. I am, of course, looking, but I am not looking in a critical way; sure, there are shadows falling across the road that create beautiful contrast, and the long, endless road in front of me, but for now, that is just enough. I am totally fine with that. In a nutshell, I am just seeing things for what they are right now.

But here is the difference between passive looking and active seeing. When my photography hat goes on my baldy head, I am not only protecting it from the sun; I have also shifted into a new mindset. Those long shadows I mentioned now have the potential to tell a deeper story because the shadows they are cast from are from a dilapidated ruin that is off the side of the road. The small vineyards in the field that have lost all their leaves now tell a deeper story of the hardship and labor that was put in during harvest. All these elements combined have the potential to make a standout image, if for no one else but you. It is a snapshot in time that was considered and, through compositional searching, essentially pre-visualized from the moment I stepped in front of the scene.

The Brain's Filtering Mechanism

So, not to get overly nerdy, but our brains have a filtering mechanism that is also known as sensory gating. It is basically an impulse for us to filter out irrelevant information in what our eyes see, but here is the catch: in order for your photography to progress, you have to learn to override this sensation and force your mind to notice smaller details—patterns in the sand, for example—and fleeting moments of light that would otherwise pass you by in the blink of an eye, or that the average person might simply ignore. If you are able to force yourself past this while in an active seeing state, then you have put yourself in the position to potentially capture the best element of the scenes around you.

The 10-Minute Reset: A Practical Way to Hack Your Brain

I know, I know. You’ve got the latest mirrorless wonder hanging off your shoulder, and you want to start clicking. But if you want to actually “see” the scene, you need to let your brain get bored first.

Next time you’re out, I want you to try this: Pick a spot—it doesn't even have to be a “beautiful” one. A quiet street corner or even a patch of woods will do. Set a timer on your phone for ten minutes, and do not take your camera out of your bag. For the first three or four minutes, your brain is going to do that “sensory gating” thing I mentioned. It’s going to tell you, “Yeah, that’s a tree, that’s a fence, there’s a car, nothing to see here, let's move on.” That’s your survival brain talking. It wants efficiency.

But stick with it. Around minute six or seven, something weird happens. You’ll start to get bored of the “big” objects, and your brain will finally start letting the filtered information through. You’ll notice how the light is catching the jagged edge of a leaf. You’ll see the rhythm in the way the shadows from a fence post are falling across the gravel. You’ll see the tiny splash of color in a weed growing through the pavement. Once the ten minutes are up, then take out the camera. You’ll find that you aren't just “looking” for a shot anymore; you’re capturing something you’ve actually seen.

2. Training the Eye: Composition Beyond the Rule of Thirds

I'm sure we are no strangers to the stoic and long-enduring Rule of Thirds when it comes to composition and photography. Following this guideline has been a standard for so many years throughout this art form's existence, and while it does have some very aesthetically appealing enticements, sometimes strictly adhering to this rule can often result in almost predictable and safe images. I am sure we have all encountered this situation when we arrive at a location: the Rule of Thirds can sometimes hinder the type of image you are looking to create. Getting a solid understanding of visual weight, balance, rhythm, and tension from a scene is paramount to creating the images you set out to create in your pre-visualization stage.

One thing that I really enjoy doing when arriving at a scene is to simply break it down into its strongest graphical elements. At first glance, yeah, sure, it's mountains and trees, and they, of course, are breathtaking, but looking at them as shapes, lines, and tones, we then start to see this scene as something completely different. The mind can start to weave together something coherent, structured, and understandably pleasing. I will use this wave photograph as an example: the Rule of Thirds is right out the window for this. There is nothing to place on any of the lines, but what the image holds for me personally is power, energy, and a feeling that the ocean is in an uproar.

Negative space is also a wonderful resource photographers can use when composing and seeing images. It's wonderful because it has a “no-camera” excuse; it's all an interpretation of what you are actively looking at and trying to frame using the tool in your hand. I am going to use this photograph of an elephant I took recently while leading a photography workshop in Namibia. There is massive intention behind this frame. I wanted to convey a sense of grandeur to the landscape and the isolation of the elephant; for me, it resonates as a sense of loneliness in the overall scene, and I love it for that.

As cliché as it may be, doing the classic “put your hands up and pretend like it's your viewfinder” maneuver may cause some heads to turn and look at you quizzically, but it is a wonderful resource to take advantage of while in the field. It allows you to quickly and effectively make very minute changes to compositions without even picking up the camera in the first place. And as we discussed, pre-visualization is so important here as well because in your mind you are already cropping, processing, and feeling the final image. I know not everybody has the ability or time to do this, but one thing that helps me immensely is to simply observe the world around me as the light changes—we'll call this the “one-hour stare.” Subtle changes in light viewed over this time can greatly impact your composition, the mood you are trying to portray, and, of course, the final result. So, if you can, stop and stare for a while.

3. The Necessity of Constraints: Removing the Gear Excuse

There is simply no question about it: there is a paradox of choice when it comes to modern digital photography. Everything from new camera cycles to lenses, accessories, and memory cards—you name it. There is a plethora of almost overwhelming choice for us in this art form. This, at least for me, can sometimes manifest itself as a limitation to my own creative output because, at times, when I struggle to find an image that I really like, it's very simple to blame the gear that I am using when, in reality, it is my own ineptness that is stopping me.

But we can look at this from a different perspective and use this overwhelming choice as a tool to expand our creative visions. There are things that we can do and locations we can approach by giving ourselves creative constraints that will only aid in our progression as photographers. These are certainly rehashed ideas, but ones worth reiterating to help you if you feel the same as I do.

Heading out the door with your camera and simply one lens—primarily a prime lens or fixed focal length—gives you a wonderful creative constraint. This very much forces your hand to think a little deeper about the images you want to create. You simply have no choice but to walk closer or further away from your subject, thus giving you a deeper connection to the results. Setting your camera to preview in monochrome is also a wonderful creative constraint, as this forces you to see simple tones and allows you to compose around those. I did exactly that on a recent workshop to Kolmanskop in southern Namibia, and it was like I was brand new to photography—a very exciting challenge.

I have discussed this in the past in other articles I have written here on Fstoppers, but focusing on a very tiny location can yield wonderful results. Take your back garden as an example; there are lots of opportunities to photograph out there. Staring for one hour might be a bit easier for you to accomplish there and give you an opportunity to train yourself to look at how everything—as simple as your backyard may seem—changes within that hour. Then take photographs. This is a highly recommended experiment.

4. The Philosophy of Intent: Finding Your Unique Perspective

So while gear matters, it really is not the end-all and be-all of this art form and your own creative expression. When the “GAS” (Gear Acquisition Syndrome) hits, potentially think about how you could spend more time thinking about your photography instead of spending money on your gear. Defining your own unique personal vision is paramount to your growth as a photographer.

There are simple questions you can ask yourself when arriving at a location as a form of self-expression: What is the photograph about? Is it a documentation of the scene or an expression of a feeling? The answer to this question usually determines the level of “seeing” involved.

There is also a huge emotional connection to consider. Your own personal history, emotional state, and cultural background all shape how you see a scene when arriving for the first time or the hundredth time. Let's call it your own personal ND filter. This is the magic and the secret sauce that AI and generic advice can never replicate. You do you.

To Sum It All Up

As we finally come to our close on this, I would again just like to reiterate that your vision will always outweigh the gear that you hold in your hands. The camera is simply the pen with which you write your poetry. A good photograph, to you, is a successful translation of a deeply personal vision that you may have; it's not as simple as a technical achievement that is captured on a “very expensive camera.”

Call to Action: So if you have made it this far, thank you, and I will leave you all with an assignment, or homework, if you will. Take your most expensive camera and lens in a bag out into the field. When you arrive there, leave the bag in the car and force yourself to use your phone to take pictures. Let your eyes and mind do all the heavy lifting, and capture something beautiful.

.png)

3 hours ago

2

3 hours ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·