Alfred Hitchcock, the director behind some of the best films ever, supposedly said that just three essential ingredients are needed to make a great film: “The script, the script and the script.” For a film-maker, it might seem a godsend when a fully formed one lands in your lap. But behind a rising number of films is a simple hack: pinch all your dialogue from real people. An increasing number of film-makers are turning to transcripts and recordings to re-enact episodes on film, with the promise that they are as an exact a facsimile as possible. From Reality (2023), Tina Satter’s true-to-life portrayal of whistleblower Reality Winner, which progresses in real time from harmless small talk to a full-blown FBI grilling, to Radu Jude’s Uppercase Print (2020), in which a rebel teen is given the third degree in Ceaușescu-era Romania, the title-card proclamation “inspired by true events” is being taken to a wholly literal new level.

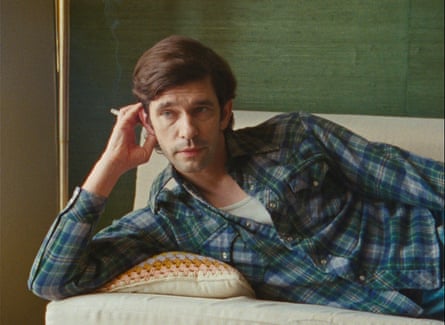

Within the space of a month, two more “verbatim” movies are in UK cinemas. Peter Hujar’s Day, Ira Sachs’ time capsule of 1974 New York and its colourful culturati, is based on candid conversation between Linda Rosenkrantz (Rebecca Hall) and her photographer pal Peter (Ben Whishaw), who would die from an Aids-related illness less than a decade later. Meanwhile, Kaouther Ben Hania’s The Voice of Hind Rajab is set in January 2024 amid the evacuation of Gaza City, revisiting beat for beat an emergency call centre’s attempts to rescue the six-year-old girl of the title to harrowing effect.

There is a precedent in the industry for following sources to the letter. Films including Sophie Scholl: The Final Days (2005), Conspiracy: The Trial of the Chicago 8 (1987), The Beast (2023) and even Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) have all flirted with word-for-word adaptation, but the first bona fide verbatim feature film came as far back as 2015. London Road was stage director Rufus Norris’s second feature; adapted from the National Theatre’s 2011 production of the same name, it is a curious tale of community spirit sparked by the grisly Ipswich serial murders, featuring a curtain-twitching Olivia Colman and a taxi-driving Tom Hardy. Adam Cork and Alecky Blythe’s script repeats what the real residents of London Road said in the aftermath of the killings, making the bold creative decision to set their remarks to music.

It is not unusual for verbatim adaptations to have theatrical roots. Uppercase Print started out as a play by Gianina Cărbunariu, while Reality Winner’s interrogation transcript (originally leaked to Politico) was first repurposed by Satter for her 2019 theatre performance Is This a Room. On the stage, the genre has a long lineage, with the idea of a “living newspaper” going back to the 1930s Federal Theatre Project in the US, which tackled hot-button topics during the Great Depression. The House Committe on Un-American Activities hearings of the 1950s also provided the fodder for Eric Bentley’s acclaimed early 70s play Are You Now or Have You Ever Been?

Interestingly, the verbatim style has crossed from stage to screen at a moment when hybrid documentaries – an experimental form straddling fact and fiction – also seem to be gaining traction. (This year’s contributions include Fiume o Morte!, Blue Heron and The Wolves Always Come at Night. More widely, 120 documentaries and non-fiction films were released in UK cinemas in 2025, according to figures from box office analysts Comscore, grossing £8.6m – an admittedly tiny 0.8 percent of 2025’s UK total of £1.07bn – but still significantly better than 2001 when just four documentaries were shown in cinemas. Fiction film-making undeniably still dominates.

Reality is often stranger than fiction, so perhaps film-makers have concluded that packaging real events in a wrapping of drama is the best way to grab viewers, cut through the noise of the news cycle and address hard truths. Transcripts that hold dramatic potential require minimal editing, with the speakers helpfully listed, as Satter observed, “like characters in a play”. Thanks to Hujar’s natural eloquence, Sachs needed few tweaks for a poetic script. Ben Hania also said that no alterations needed to be made to Hind Rajab’s story, since what is unfolding in Gaza is “something that is beyond fiction”.

Another hallmark of the new verbatim wave is vérité cinematography, featuring closeups, handheld cameras and natural lighting, designed to create a sense of immediacy and direct engagement with the film’s subjects. The Voice of Hind Rajab combines dizzying closeups of its cast along with actual recordings of the girl at its centre. There is an obvious appeal in hewing near to reality when current events are increasingly harder to reckon with. In Ben Hania’s film, verbatim performances and recordings are an important part of being faithful to Hind’s story and enabling her to be heard – with a voice that speaks for itself.

.png)

2 hours ago

2

2 hours ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·