“Okay, so you’re tied to a chair inside a run-down trailer,” the game master told me. “The woman standing in front of you punches you in the face. ‘Where is it?’ she screams. ‘You’re going to tell me, or I’m going to hack pieces off of you until you do!’”

I blinked. I’d been handed a character sheet just 20 minutes earlier. The only thing I knew was that I was the leader of a biker gang. There had been no lead-up, no introduction to the world of this tabletop RPG. I didn’t know who this screaming woman was, how I’d ended up trapped in her trailer, or even whether I had the information she was trying to beat out of me.

And I loved it. I wasn’t used to getting thrown straight into the deep end this way, not even at the kinds of indie-RPG one-shot showcases I’d been frequenting, where weird formats and radical narrative experiments were the norm. Being introduced to a story that was already well underway and facing a dangerous situation with a lot of unknowns was an exciting, startling challenge that I still remember more than a decade later, long after most of the other details of that one-shot have faded. That cold open pushed me out of my comfort zone, started the game with a bang, and instantly focused the attention of everyone at the table. Suddenly, we weren’t a bunch of strangers trying to figure out how we wanted to approach this game: We were a team dealing with an urgent, immediate, life-or-death problem.

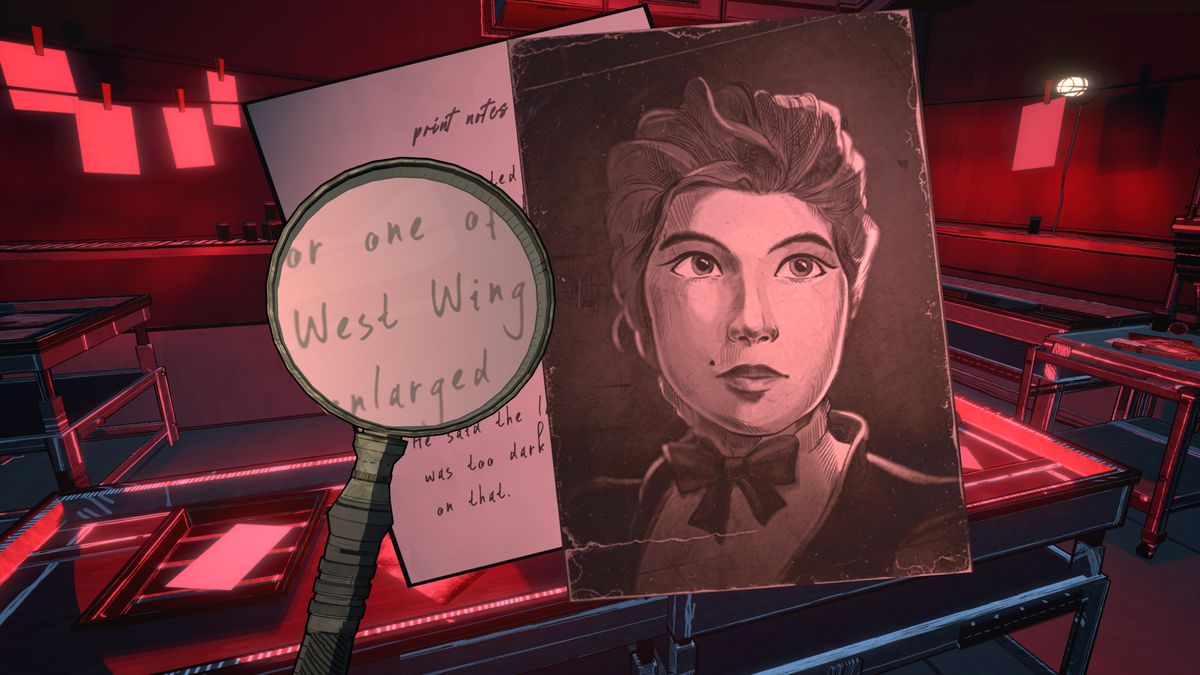

Image: Evil Hat Productions

Image: Evil Hat ProductionsTabletop RPG narratives that start in the midst of the action are pretty atypical. The published D&D campaigns I’ve played or run tend to open with low-stakes scenarios that acclimate characters to a setting or situation. Most of the non-D&D campaigns I’ve played (or run) over the years start with some form of slow-burn relationship-building, akin to what Critical Role’s Campaign Four did at launch, with a lot of lore and characters figuring out their motivations and connections. I’m often drawn to collaborative storytelling games like Dialect or The Quiet Year, which focus as much on collective world construction as they do on actual playtime. My favorite horror game to run is Dread, which starts with players filling out questionnaires to define their characters — often a lengthy, thoughtful writing process before anything else happens.

But as much as I like the character-first or shared world-building style of play, there’s a real thrill to games designed to thrust you right into the middle of a high-stakes, intense scenario — games that skip all the cautious party-planning and pondering, the negotiation and debates and anticipation, and get straight to the moment where important decisions have to be made, fast.

Lady Blackbird, the all-time great pick-up-and-play game by Blades in the Dark designer John Harper, is one of my all-time favorites. It's expressly designed for urgent, immediate story action. The pre-gen characters (instantly recognizable iconic space-fantasy hero types, inspired by a mash-up of Star Wars and Firefly) start out captured by evil Imperial forces, and then have to use their wits and skills to escape the Imperial cruiser Hand of Sorrow. The system is intuitive and designed for easy understanding and a low barrier to action, but the way the story starts with the characters already deep in trouble with a clear goal puts Lady Blackbird among the best one-shots I’ve ever encountered.

Image: John Harper

Image: John HarperI’m guessing Harper likes in medias res games in general: His one-shot scenario Magister Lor similarly begins in the moments after a vengeful apprentice releases a bound demon. And Blades in the Dark is a heist-driven game designed so players can act first, then justify their actions by revealing their planning afterward. Games inspired by Harper’s work often share this element: Will Hindmarch’s Always/Never/Now is a cyberpunk re-imagining of Lady Blackbird that opens with the characters arriving at a crucial server facility that holds information they need, but they're immediately forced into combat against the data-thieves that are ransacking it.

Another longtime favorite “act first, then figure out the world around you” RPG is Meguey Baker’s Psi*Run, a simple, infinitely reskinnable game built around a basic framework: The PCs have amnesia, superpowers, and powerful enemies chasing them. I’ve played Psi*Run as a fae-centric fantasy game, a cyberpunk story, an X-Men-esque mutant superhero story, and more. But no matter how you flavor it, the game begins with a dramatic, destructive event (called “a crash”) that frees the players (“Runners”) from their former captors (“Chasers”) and launches their escape while they're being pursued. The game text begins, in suitably dramatic form, “It starts with the smell of melting plastic. The angles are all wrong, and there are sounds of pain, human and machine. The taste of adrenaline coats your tongue. Get out. Get out! RUN!”

Amnesia scenarios — where players have to figure out their identities, the world, and their predicament within it — are great pretexts for these kinds of action-first games. But amnesia isn’t a necessary part of the story. It’s often enough to just have a relatively simple, straightforward scenario everyone can immediately follow. Just look at Grant Howitt’s horror-action game Eat the Reich, where players start as a group of vampire commandos stealth-dropped out of a plane and into occupied Paris during World War II with the goal of “drinking all of Adolf Hitler’s blood.” Howitt is another designer who specializes in these in medias res scenarios: My personal favorite of his is Death Was the Only Road Out of Town, where the PCs are noir anti-heroes in a dark, corrupt city. But they’re aware that they're inside a dream that someone else is having. A series of dice charts generate the scenes, so players can launch right into the scenario that will lead them to confront, and if possible, kill whoever trapped them in the dream.

Image: Rowan, Rook & Decard

Image: Rowan, Rook & DecardThere’s no reason Pathfinder or D&D stories can’t start in the middle of the action, either, especially if players are bringing in characters they’ve already played, or the story starts in a familiar setting that doesn’t need build-up and acclimation. The flexible fan-favorite adventure “Claus for Concern” starts with a group of Santa’s elves crash-landing his sleigh anywhere the GM wants as they seek help with a North Pole invasion. The Worldwound Incursion, the first adventure in Pathfinder’s Wrath of the Righteous arc, opens with a demonic incursion tearing open a hole in the city of Kenabres, sending the PCs plummeting into the underworld. The 5E adventure Hoard of the Dragon Queen similarly begins with the PCs walking into a town that’s under attack by a dragon and “a small army” of cultists, bandits, and mercenaries stealing everything they can grab to present to their queen, Tiamat.

This style of tabletop storytelling does have its downsides, however. Even more than most RPGs, they require a confident, well-prepared GM who’s good at rolling with unexpected player decisions and filling in the gaps for confused or hesitant players on the fly. Players who prefer collaborative world-building, or who get anxious if they feel rushed into decisions or put on the spot, may feel shut out by this style of play. And action-first games often aren’t great for character-first experiences, unless everyone embraces the idea that their characters are either in a stressful situation that will let them connect with each other quickly, or that they have an established shared history that they can create after the fact. (Games like Lady Blackbird and Psi*Run have flashbacks mechanics built in for this kind of retroactive character construction.)

Such an approach can prove divisive. I’m currently playing a Star Wars: Edge of the Empire campaign where the GM loves to start sessions mid-combat, then justify the decisions that brought the players into that situation after the fact. That approach skips a lot of the “Where do we go / What do we do next?” discussions that can eat up play time, given the size of our sandbox galaxy and the wealth of options in front of us. But it also steals some of our agency. In that one-shot where I started the game tied to a chair getting shaken down for information, I had to immediately wonder, “Is the character I’m playing stupid or careless? How did he get himself into this situation?”

Image: Paizo, Inc.

Image: Paizo, Inc.But if your play group is anything like mine — or like a lot of the players I’ve encountered at pickup game nights or convention events — one of the more challenging aspects of one-shot RPGs can be getting to the exciting part of the story. Sometimes players want to overthink their plans before making risky moves, gaming out every possible scenario in advance. Sometimes the path to an important confrontation isn’t entirely clear. Players might even be hesitant to get involved in an obviously dangerous situation, either out of an abundance of caution, or because they’re playing characters who wouldn’t charge into danger. (Often, those players want to be pushed into danger anyway, for comedic or dramatic reasons, but they won’t take the leap on their own.)

And sometimes, especially as a GM, you just have limited time for a play session, so you want to skip the preliminaries and jump straight to a key moment in the story. Cutting straight to the chase — literally, if your cold-open action scenario is a chase scene — is a lot like eating dessert before dinner. It can be self-indulgent, and it isn’t necessarily the right choice for every meal, or every diner. But it can be a lot of fun for a once-in-a-while treat.

.png)

10 hours ago

3

10 hours ago

3

English (US) ·

English (US) ·